“The prince is dead, the prince is dead!” – Remembering Rubén Darío

Madrid exhibition observes 100th anniversary of the death of Nicaraguan poet and diplomat

The paperboys in Madrid’s central Puerta del Sol square shouted out the tragic news that chilly February morning in 1916: “The prince is dead! The prince is dead!”

The deceased heir to the throne was in fact a Nicaraguan-born poet and diplomat, Rubén Darío, who had passed away at the tragically young age of 49 at the height of his powers as the founder of the modernist movement, a literary style in which he had played a leading role.

When Darío passed away, Francisca married and started a family, working hard to preserve the poet’s legacy

Hearing the tragic news, Francisca Sánchez, his lover for two decades and who had said goodbye to Darío a few months earlier, wept as she held their child in her arms, and sent her sister down to buy a newspaper.

Darío had been in poor health in 1914 when he sailed to the United States on a peace mission at the outbreak of World War I, leaving Sánchez behind in the Spanish capital. In the preceding years she had followed him tirelessly from Paris to Barcelona and then to Madrid, taking not only their belongings back and forth, but keeping her mother and sister in tow.

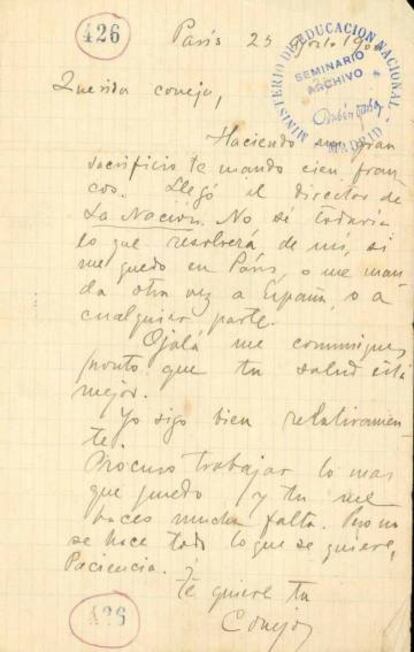

Among those belongings were an old trunk where, to the end of her days, she kept all the documents pertaining to the man she fell in love with “through his words,” recalls her granddaughter, Spanish journalist Rosa Villacastín.

An exhibition at the library of Madrid’s Complutense University sheds new light on the life of Darío, helping reconstruct the 20 years he and Sánchez spent together.

There are copies of the modernist magazines that he edited such as Mundial Magazine or Elegancias. There are also exchanges between the writers within the modernist movement: in one, Spanish poet Manuel Machado chides Darío for his poor management of Mundial Magazine. Another letter suggests he abandon writing and open a bakery. There is also a menu with dishes named after Darío’s work that were served at a gala dinner in Argentina in 1912. And there is a note from his friend Rufino Blanco Fombona, asking him to attend a duel.

A womanizer and bon vivant, Darío abandoned his wife in Nicaragua after a lengthy drinking session. He fled to Spain and found refuge with Francisca Sánchez, who is shown in all the photographs of the couple wearing a black, high-necked dress. Her unmarried relationship with Darío caused a scandal in a deeply conservative, Roman Catholic society.

The poet was unable to divorce his wife, but he lived for the last two decades of his life with Francisca, and had four children with her, three of whom died in infancy.

The Madrid exhibition includes some of Darío’s many bar bills, receipts for his road trips across several countries, and a simple-looking oilskin notebook that is particularly significant “because it reveals how he wrote on a day-to-day basis,” explains Rocío Oviedo, a lecturer in Latin American literature at the Complutense University.

In some ways, the notebook sums up the author’s entire home life within a few pages. There are handwritten poems, complete with corrections that help scholars understand Darío’s creative process. There are also drawings by his son, as well as notes added by Sánchez.

In one letter, his aunt asked him to reform so she could die in peace

Considering his itinerant lifestyle and taste for the nightlife, it is hard to imagine how Darío found the time to write so many books and poems, edit magazines, participate in conferences, deliver lectures, and work as a diplomat to boot.

The exhibition suggests that his style of life would catch up with him sooner or later, illustrated by a telling letter from his aunt, whom he called Mamá Bernarda, begging him to reform so she could die in peace.

When Darío passed away, Francisca married and started a new family that worked hard to preserve the poet’s legacy. The trunk and its 5,000 documents were eventually donated to the Spanish state.

English version by Susana Urra.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.