“My father was much crueler than the Pablo Escobar you see on Netflix”

Son of Colombian drug lord accuses TV series of glamorizing life of man responsible for 3,000 deaths

“It’s full of errors.” That’s the verdict of Juan Pablo Escobar when asked about the hit Netflix show Narcos, which recounts the story of his father, the notorious 1980s Colombian drug trafficker Pablo Escobar.

But instead of complaining about the series’ brutal portrayal of his father, who was gunned down by police in 1993, ending his career as the main trafficker of cocaine into the United States, he believes the reality was far grimmer.

“My father was much crueler than he appears in the show. He terrorized an entire country,” says Escobar’s oldest son, who now goes by the name of Sebastián Marroquín.

In the series I’m like Benjamin Button. I get younger and younger: by the end I look about eight years old Sebastián Marroquín, Pablo Escobar’s son

“You have to be responsible when telling this story. There are thousands of victims [in Colombia] who deserve respect. The show creates a culture where being a drug trafficker is cool. Young people all around the world write to me saying they want to be drug dealers and asking for help. They write to me as if I was selling tickets for entry into this world,” says an angry Marroquín.

But what most annoys the 39-year-old about the Netflix version of his father’s life is that it claims to be realistic.

“It doesn’t show the moments of loneliness, fear, anxiety and terror. The violence was far worse than the show suggests. I am not proud at all, but we have to be serious,” says Marroquín, who offered, but was turned down by Netflix, to act as an advisor on the show – a role that would have allowed him to provide his first-hand insight into what was a virtual civil war in Colombia, after Escobar launched an offensive against the rival Cali drug cartel in the late 1980s in a bid to control the hugely lucrative cocaine trade.

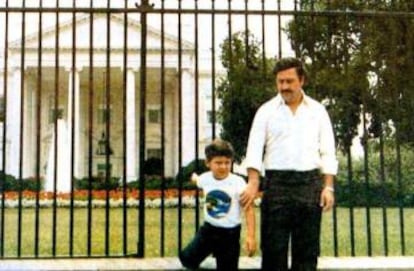

Escobar’s son provides concrete examples on how he thinks the show got it wrong. “We didn’t live in luxury when we were on the run. I wish we had had the houses with swimming pools you see in the series. And we weren’t surrounded by gangsters either. We were very much alone, because everyone betrayed [Escobar] or gave themselves up. Or they were killed.”

My father was much crueler than he appears in the show. He terrified an entire country Sebastián Marroquín

The son of the man who at one stage controlled 80% of the cocaine going into the United States also describes a life constantly on the move. “Sometimes we would buy a house and then we would have to move the same night, and the money would go down the drain. We always traveled with blindfolds on. That way, my father always said, if we were captured and tortured we couldn’t give him up,” Marroquín explains.

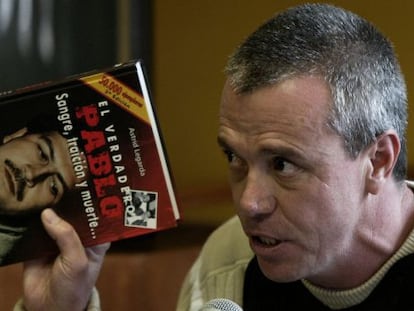

“He didn’t use telephones either. My father said it was certain death because he had always found people he wanted to kill by tracking their phone calls,” adds Marroquín, who has written one book about his father and is now working on a second, which focuses on the final few months of the drug trafficker’s life when he was no longer with his family.

28 ways Netflix gets it wrong

Neither is Escobar’s son impressed with the young version of himself that appears in the show.

“To start with, I wasn’t a child. In the series I’m like Benjamin Button. I get younger and younger. By the end I look about eight years old. But I was 16 when my father died. I knew everything that was going on. He always told me he was a bandit and a gangster. We watched television and he had no hesitation in telling me, ‘I planted that bomb.’ And we would argue about it.”

Marroquín has drawn up a list of 28 serious errors on the part of the makers of the Netflix series – a list that includes scriptwriters getting it wrong as to which soccer team Escobar supported and the false inclusion of a scene in which the gangster raised in Medellín burned banknotes to keep the family warm.

“Once I said in a documentary that we were starving while we were surrounded by millions of dollars. And that is true. Once we were surrounded by the police and we didn’t have any food for a week. I said then the only thing the money was good for was throwing into the fire. But we never actually did it.”

Marroquín insists that his father committed suicide once he was surrounded by the police, and that in the aftermath he and his mother had to negotiate with the Cali cartel to avoid being killed. “They told us we would have to live outside the country. They demanded we hand over all of our assets as war booty. They knew exactly how much money my father had. The message was simple: if we hid even a single coin they would kill us. That’s how we saved our own lives.

“I had to start from zero,” he adds.

Investigators didn’t believe this story and Marroquín’s mother spent two years in prison on money-laundering charges. Marroquín himself spent 45 days behind bars before being found not guilty of any wrongdoing. He then moved to Buenos Aires where he lived in relative peace – or did until the Netflix show revived interest in his story.

Escobar’s son says he’s not interested in restoring his father’s reputation, and instead just wants people to stick to the facts as he knows them.

“Let’s not lie. My father killed 3,000 people. The real story has enough violence, explosions and terror. We don’t need creative scriptwriters to sex it up with lies.”

English version by George Mills.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.