How Russian networks worked to boost the far right in Italy

An analysis of social networks reveals how Kremlin-backed media outlets boosted xenophobic discourse

The Russian meddling machine has been focusing on Italy in recent months, conducting a disinformation campaign on the migration situation in order to drum up support for radical parties ahead of the general elections scheduled for Sunday.

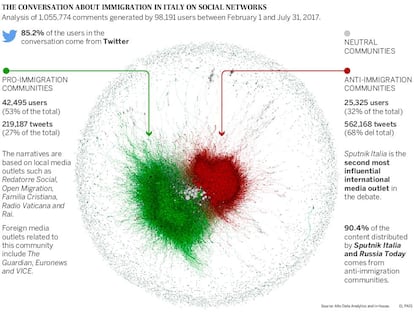

According to an analysis of 1,055,774 posts from 98,191 social media profiles to which EL PAÍS has had access, a network of anti-immigration and anti-NGO activists has been sharing links of stories published mostly by Sputnik, a media organization owned by the Russian government and operating in Italian among other languages, in order to propagate a false image of Italy. In this scenario, the country has been invaded by refugees who are to blame for unemployment and inflation, in the midst of a crisis made only worse by the passive attitude of pro-European politicians; ultimately, the European Union itself is held up as a culprit.

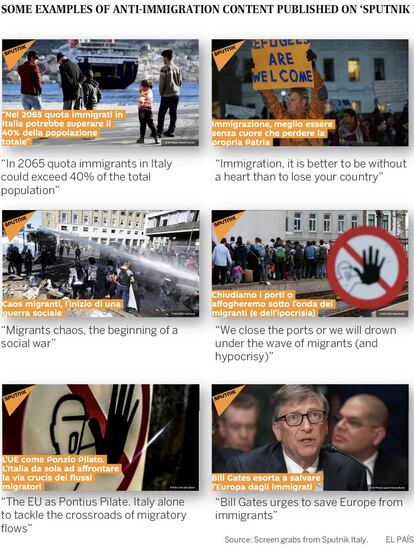

A few examples of stories run by Sputnik include: “In 2065, quota immigrants in Italy could exceed 40% of the total population,” and “Migrant chaos, the beginning of a social war.”

Alto Data Analytics, a global company that uses big data and artificial intelligence to analyze public opinion in the media and social sites, showed this newspaper a study of 3,164 sources containing news, blog posts and videos published between February 1 and July 31, 2017.

The conclusion is that Sputnik Italia has been very influential in radicalizing the public debate over the immigration crisis. Of all foreign media operating in Italy, Sputnik was the second-most influential, following the Italian version of The Huffington Post, according to Alto Dato Analytics, whose algorithms rank websites by user numbers and intensity of shares on social media, much like Google’s algorithms.

Increasingly successful radical speech has replaced nuanced debate, which has been conspicuously absent for months

The immigration debate has become the central issue of Italy’s campaign, which has hardly touched on other topics. Surveys show that any party without a clear position on immigration will be left out of the picture on Sunday. This situation is reflected by tension on the streets and on social media, where nuanced debate has been conspicuously absent for months, and replaced with increasingly successful radical speech.

The rise of the League, a party with xenophobic tendencies headed by Matteo Salvini and part of a powerful center-right coalition led by Silvio Berlusconi, or Casa Pound, an openly fascist group that hopes for a spot in parliament, are just two examples.

Sputnik was a key player in the strategy of Italian destabilization, but it was not the only one. There was another network of small websites focusing almost exclusively on anti-immigration messages such as “All the Immigrants’ Crimes,” “The Populist” or “Italy, my homeland.” An indication of activity by automated accounts, or bots, which are used to make content go viral, is that with twice as many members, the pro-immigration community still published less than half as many comments as those posted by anti-immigration users. Within the sample period, anti-immigrant profiles on Twitter created 68% of all comments on the topic.

90% of those who shared Sputnik content were profiles who regularly disseminate anti-immigration messages in Italian

The Russian misinformation networks used the same pattern in this case as in the past: questionable sources, biased experts and sensationalist headlines that were shared by tens of thousands of accounts with the goal of making the content viral and amplifying the perceived problem. The UK parliament is analyzing Russian influence on the Brexit referendum, and the Spanish Congress is doing the same with regard to the secessionist crisis in Catalonia. In the US, a special counsel is investigating Russia’s role in the 2016 presidential elections.

In 2016, when the immigration crisis reached a climax with 181,436 new arrivals (according to Interior Ministry data), Italy was already at a critical juncture. The forecast was that there would be a further rise of 30% in migrant arrivals in 2017, a figure that fueled racist-tinged, populist rhetoric by most political parties. The trend affected the government, which was unable to push forward a fundamental law to grant citizenship to the children of immigrants. Above all, it gave wings to the more radical rhetoric spread by the League, which took control of the discourse and began rising in the polls.

How the immigration debate in Italy was poisoned

Sputnik, the Kremlin’s news agency, and the RT television channel are among the 100 most influential media outlets in terms of the anti-immigration narrative, according to an analysis by the company Alto Data Analytics, which took into account 3,100 sources of content.

Some of the headlines of the articles published by Sputnik Italia in the last year included the headlines: “Immigration, it is better to live without a heart than to lose your country.” Or: “In 2065 quota immigrants in Italy could exceed 40% of the total population.” And: “The EU as Pontius Pilate. Italy alone to tackle the crossroads of migratory flows.”

According to the analysis by Alto, the Italian version of Sputnik is the second-most-influential outlet in the Italian digital debate, only behind the US website The Huffington Post. Taking into account domestic and international media, Sputnik is in the 40th spot in terms of influence, according to an analysis by Alto Data Analytics, which is based on an algorithm similar to that used by Google to rank the relevance of websites.

The Alto study reflects the fact that Sputnik achieves a disproportionate influence in the Italian digital conversation, despite having just over 45,000 followers on Facebook and slightly more than 6,300 followers on Twitter. This impact can be explained by the very active participation of a reduced number of influential accounts of anti-immigrant users. Despite the fact that anti-immigrant users in Italy are only 32% on Twitter, their tweets represent more than two-thirds of the conversation, Alto explains.

The Italian version of Sputnik is one of the more than 30 versions in different languages from the Russian agency, which also has services in English, Spanish, German, French, Chines and Arabic. The RT channel does not have a version in Italian, but its versions in English and Spanish are followed on Twitter by millions of accounts. With its dissemination of extreme content, Sputnik and RT join a number of new digital media outlets that are contributing to the polarization of the debate, reinforcing local narratives, the Alto analysis concludes.

“Sputnik and RT have become just another source for those radicalized voters who look for any excuse to find proof that immigrants are bad,” explains Eleonora Tafuro Ambrosetti, a researcher at the Milan Institute for International Political Studies.

The data analysis shows that 90% of those who shared Sputnik content were profiles who regularly disseminate anti-immigration messages in Italian. According to Alto Data, “messages from this community closely link immigration with insecurity, crime and terrorism, and in some cases, with conspiracy theories such as the one positing that the migration crisis is part of a larger strategy to destabilize the country.”

One of the biggest fears of the current government of Paolo Gentiloni and of the social-democratic Democratic Party (PD) was that the campaign would end up being dominated by the immigration debate. It was fertile territory for the rise of the extreme right and the discourse of the League and Brothers of Italy, the two parties that form the center-right coalition, which today is leading all the polls, nearly with an absolute majority. That was why the interior minister, Marco Minniti, designed a plan with the Libyan government and the army to put a stop to the arrivals. It worked. From July onward, the Coast Guard started to take action, and arrivals fell dramatically.

In the end, the year closed with 119,369 migrant arrivals, and the social tension was notably reduced.

But on February 4, just a month before the elections, an incident saw all of that work go to waste. A 28-year-old man, a candidate for the League in a northern town, fired shots from his car at a number of African immigrants, injuring six of them. In a surprising twist, the League managed to take control of the narrative once more, and blamed the incident on the social tension caused by immigration.

In a habitual practice seen in its interference in other countries such as Germany, Russia has cultivated relationships with parties on both ends of the political spectrum in Italy. Its links with the League and the populist Five Star Movement have been evident for two years. Salvini was seen in March 2017 with Sergei Zheleznyak, in charge of relations with European parties at the Kremlin. That day an agreement that had been months in the making was signed, also via displays of admiration by Salvini for Vladimir Putin and the electoral promise of breaking with the trade embargoes against Russia, which, according to the League leader, have cost Italy €5 billion and have had a particular effect on Italian meat and textile companies.

The text speaks of “cooperation in areas of security, the defense of traditional values and future economic cooperation between Italy and Russia.” It’s an idea that can also be seen in all of the documents signed with the National Front (FN) of Marine Le Pen in France, or with the far-right Austrian Freedom Party. Both, like the League and the Five Star movement, are belligerent with the European Union.

English version by Susana Urra and Simon Hunter.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.